This article was originally published on Digital Photography School and is used with their permission.

I don’t know about you, but I was never much of a math student. I needed a tutor in high school for both geometry and physics. I chose a double major in college (Journalism/English) that required no math. I practiced law for fourteen years, where any math I needed was either pretty easy or done on a calculator. Even when I ditched my briefcase for a camera bag and embarked on a new career, I felt pretty secure in the knowledge that confusing math had no place in the world of photography.

And then the Inverse Square Law reared its ugly head.

It didn’t jump out and attack me right away. No– the Inverse Square Law is much too cunning for that. It was patient. It bided its time. It waited for me to get comfortable in my new skin a professional photographer. It waited for me to feel secure in my knowledge and execution of studio lighting and off-camera flash. And then it showed itself.

We all deal with light. It is the defining element of what we do. We capture light in a box and use it to tell a story. Some photographers put themselves in the “natural light” category, while others work their magic with a firm grasp of off-camera flash. While the Inverse Square Law comes into play more often with strobes, it is absolutely a concept that applies to every light source, and therefore affects every photographer.

So, what is it? In all of its overly technical glory, the Inverse Square Law– as it applies to photography– is an equation that relates the intensity of a light source to the illumination it produces at any given distance.

Huh?

Regardless of how you classify yourself as a photographer, you already know that light travels. It can be diffused. It can be reflected. It can be deflected. But it travels. This means that over time and distance its intensity can and will diminish. What does that mean for your photography? It means that doubling the flash-to-subject distance reduces the light falling on the subject to one-quarter. Logically, we might assume that doubling the distance would reduce the power by half. In actuality, however, doubling the distance reduces the power by 75% More simply put, the Inverse Square Law is used (among other things) to determine the fall-off– the difference in illumination on a subject as it moves farther away from the light source.

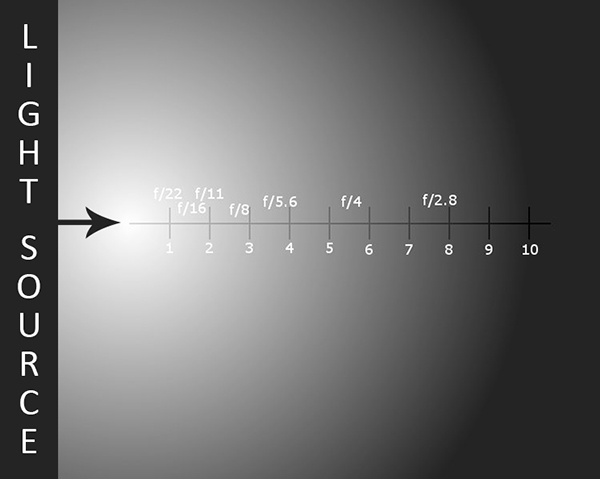

Let’s take a look at a graphic that will help us get our heads around this. We are looking at a blank wall approximately ten feet long, illuminated with a single light source. Meter readings along the wall show the progression of one-stop increments. Notice how we move one stop from f/22 to f/16 in a matter of inches, yet we move one stop from f/4 to f/2.8 over the course of a few feet.

Now that we understand what the Inverse Square Law is and how it affects the intensity of light, how do we apply it to our photography? Let’s assume that we are photographing a family of four on our wall. If we position them closer to the light– let’s say in the f/8 – f//11 range– we are going to have a lot of contrast between the subjects. Those closer to the light source catch the brunt of the light and may be overexposed, while those further from it could be underexposed. The variance in the light over such a short distance means the light falling on our subjects will be very uneven. If, on the other hand, we move our family down the wall to the 7- or 8-feet mark, we have a wider area in which to achieve a more even exposure across the group.

Remember, though, that the same principles apply not only to our subjects, but to the relationship between the light source and the background as well. If we are photographing our imaginary family with a plain white wall for a background, simply moving them closer to or farther away from the wall will affect whether the wall appears white, gray, or even black.

So far, we’ve discussed what the Inverse Square Law is and how it applies to off-camera flash. But what about natural light? The same concept applies, whether you are using window light, a reflector, a sunset, or any other non-electrical light source. The principles of how light travels do not change just because the light in question has no batteries. Doubling your subject’s distance from the window, for example, is going to result in the same 75% drop in intensity that you will experience with strobes or speedlights.

So, what’s the bottom line? The best advice I can give about the Inverse Square Law is to simply be aware of it and understand its potential impact on your photos and lighting setups. The more you understand light and how it behaves, the better equipped you will be to efficiently compose and create consistent images with less trial and error.

This article is courtesy of Jeff Guyer, a commercial/portrait photographer and photography teacher based in Atlanta, GA. You can check out more of his work at Guyer Photography, and connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.

This article was originally published on Digital Photography School and is used with their permission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.